Joseph Cross – Between Fashion and Fiction

How does our perception change when fiction looks as real as reality? Joseph Cross, senior concept artist at American Bungie pushes the magic border with his robotic characters, excelling in tricking the human eye. Originally trained in traditional illustration Joseph bounced around different areas of commercial art, teaching and retail jobs until landing the first job in games as an environment concept artist on Dead Space 2 for EA Visceral. Since then he’s been working on a variety of other projects and games including Dead Space 3 and Destiny.

What is the story behind these characters?

– All of these are personal works. If you had asked me before I started working as a concept artist what I imagined myself doing in the field, I probably would have said designing characters. But as it worked out I’ve spent the vast majority of my career as a concept artist designing environments and spaces. So that’s what these guys are born out of, years of pent up desire to design characters.

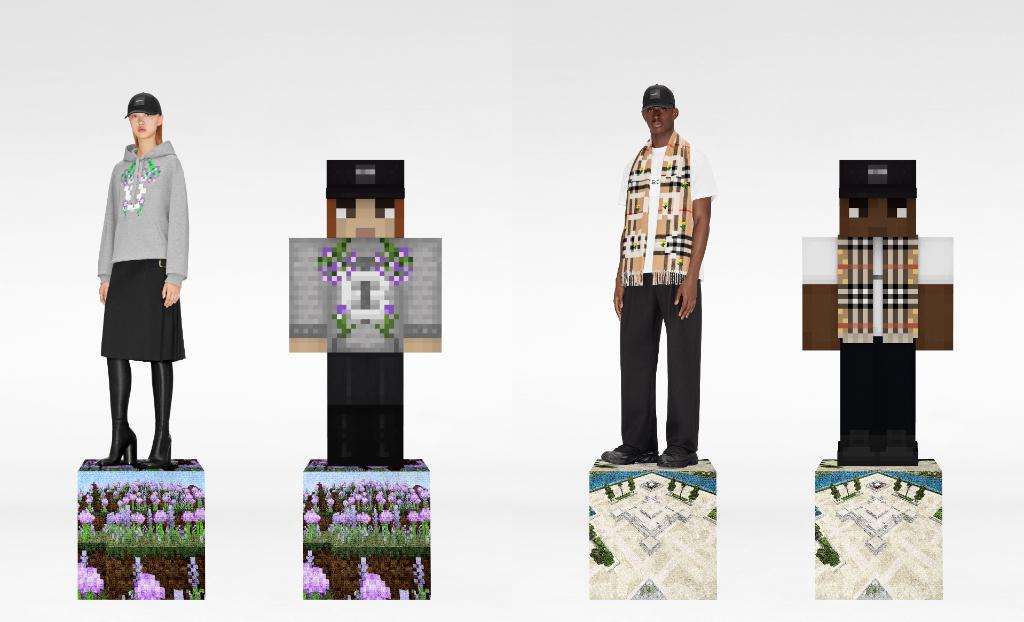

Aesthetically these characters come from a growing interest and appreciation of fashion, and being inspired by all the amazing character concepts out there. I did all these characters fairly quickly over about a month or so, and I really tried to think of them as fashion designs (as opposed to concept art) and myself as a fashion designer. It really freed me up mentally, and I tried to focus on textiles, materials, trends, color blocking, as opposed to rendering and how “cool” can I make this character.

For many of us, it’s hard to grasp that these outfits are actually 2D and not 3D looking amazingly realistic. They are also highly detailed descriptions of textiles and materials. How would you for someone outside of game context explain how you technically go about?

– I always start with a photograph in Photoshop, usually of a figure that has a nice gesture or lighting, and is not too stylized design wise, something utilitarian that will provide a nice “canvas” to work on top of. Then I’ll start searching through my library of photos that I keep of industrial objects, fabrics, textures etc. looking for things might be interesting to combine with the original photo. For example a section of an airplane wing overlaid on a figure in the same perspective might provide an interesting design idea for a helmet. Then I go through that process dozens more times, with each new element informing the next, and painting in areas of the design where the materials or textiles or lighting doesn’t match. It can be tedious, and I never really know what the end result will be, but that’s the fun of it. Spontaneity is really important for me, I love reacting to design decisions that I didn’t know I was going to make.

– In production art I like to think realism is always ideal and something to strive for, but not always required. As a production concept artist it is your job to provide visual information and inspiration to other artists whose job it is to turn that art into a usable asset or 3D environment.

-Realism=information so the more realism the better in most cases. There are definitely times when it is not required, like if an environment artist has a tight budget or schedule and just needs a couple of quick ideas for a prop or a motif for a room to slam in. Or a quick proof of concept sketch to show a particular size of door will work in a space etc. There are also concept artists who specialize in more illustrative work, and are brought into to create amazing paintings of castles and ships to inspire the story and generate ideas in a more grand sense. In that case realism certainly isn’t a requirement.

Your concepts are, as I assume imaginary futuristic. What do you think the actual future will look like in terms of aesthetics. Are the alien like, sci-fi and robotic shapes we use to describe the future ever likely to come true?

– “Predicting the aesthetics of the future” is definitely in the job description of a concept artist. It’s a slippery slope and can do your head in if you think about it too analytically, but it’s also what makes the job so fun.

– The way I see it there are a few key points or rules that I keep in mind when thinking about and designing the aesthetics of the future. These are in no way meant to be a formula for predicting the future of design, but I think they are valuable things to keep in mind if you find yourself in the position of having to do so for a living:

1: Design is cyclical

2: There are periods of design that are objectively outstanding/superior to others

3: Life imitates art

– So in practice I try and apply those points like this:

For whatever point in the future you happen to be designing for or thinking about, it is reasonable to draw aesthetically from some point in the past (or present).

– Whether it’s art, architecture, graphic design or industrial design, when drawing from the past or present make sure you have educated yourself thoroughly in as many fields as possible, so that you can make intelligent, informed and creative choices for your references.

– Have confidence in your ability as an artist and visionary and know that artists have always had a profound influence on industries outside of the medium.